The application of anatomy to shibari lies in understanding how to use it to our advantage to enhance the experience and reduce the risk of injuries during practice.

Physical safety—avoiding dreaded injuries or at least minimizing their risk—is often the first thought that comes to mind when we combine anatomy and shibari in a sentence.

That’s a good sign. It shows you are empathetic and care about safety, likely focusing specifically on the physical well-being of the person being tied.

However, I regret to inform you that this perspective is overly simplistic.

Just as safety in shibari isn’t merely about carrying a first-aid kit in your backpack, body techniques are not solely about preventing injuries. Injury prevention is more a consequence of correctly applying these techniques rather than their sole purpose.

The primary role of these techniques is the proper handling of the body to generate organic, natural, and fluid movements. Their application begins with the body of the person tying (first), eventually transferring to the body of the person being tied (second).

In other words, correct taijutsu application must originate from the person tying, including their posture and movements. Only then can the technique be applied to the person being tied, following the same principles.

This sequential approach promotes smooth and organic movements while reducing injury risks. But remember, injuries can have multiple causes; anatomical management is just one of them. Overconfidence is not advised.

Mastery in managing both one’s body and another’s greatly enhances the shibari session, allowing bodies to express what individuals are experiencing at the moment.

When studying taijutsu techniques, we approach shibari as an anatomical restriction reinforced with ropes, always within an erotic context.

Other contexts, such as photography, acrobatics, or performances, may have different specific requirements. Training includes basic anatomical and biomechanical concepts applicable to any of these settings.

Our guidance is never a substitute for professional medical advice.

Understanding

To begin studying taijutsu and safely practice shibari, the first step is understanding the body—its structure and function.

This knowledge helps us become aware of its capabilities, limitations, and the risks of manipulation, as well as how to prevent those risks and utilize both our own body and that of our partner to our advantage.

Let’s start by acknowledging that every body is unique, with its own physical condition that fluctuates over time.

This support material provides general advice that is personalized and adapted in our one-on-one consultations. This approach allows for a shibari practice tailored to the body, adjusting to the individual’s condition at any given moment.

Anatomy and biomechanics offer valuable insights for the safe practice of shibari. We encourage you, as much as possible, to invest time in their study and, more importantly, in nurturing your body.

In taijutsu studies, we combine martial arts techniques, particularly from Aikido and Tai Chi, with scientifically backed concepts and methods.

Each of these disciplines offers a unique perspective on anatomy and the human body.

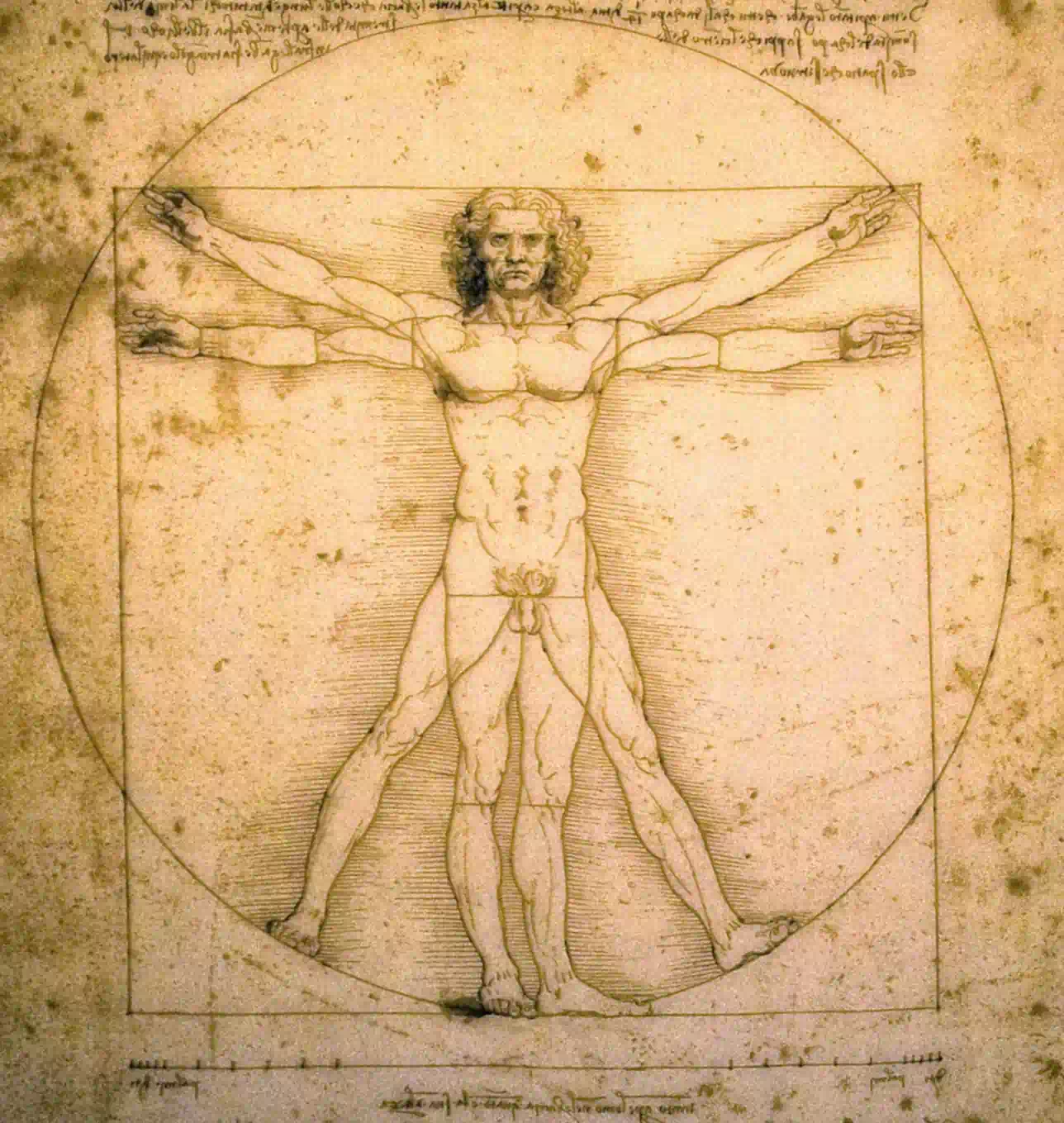

In Western culture, the anatomical model is often represented by Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, valuing space through the concept of the golden ratio.

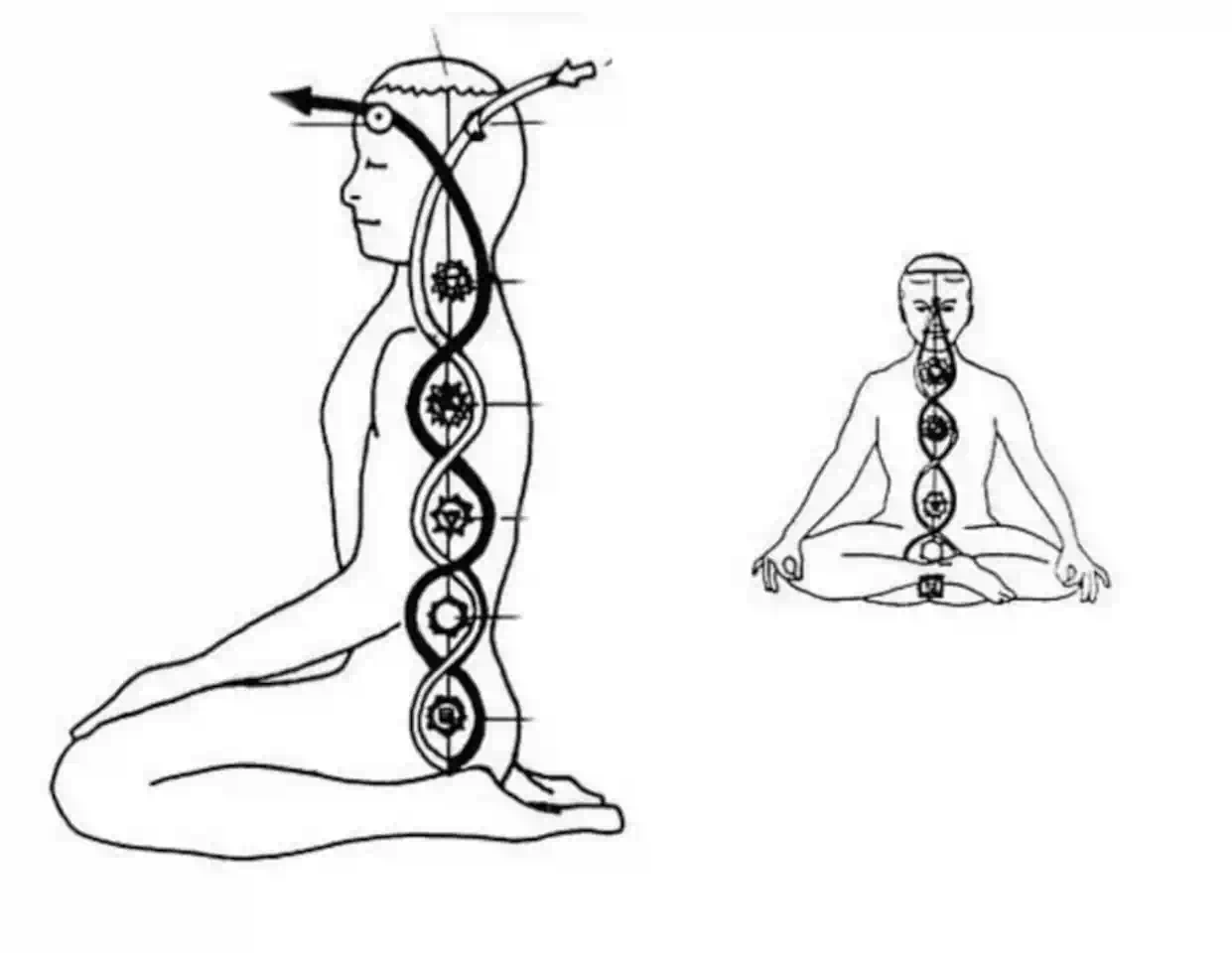

In Eastern cultures, particularly those influenced by Traditional Chinese Medicine, the anatomical model differs. It is seen as a spiral encompassing both the physical body and the energies flowing through it.

In Eastern cultures, particularly those influenced by Traditional Chinese Medicine, the anatomical perspective differs significantly. It is envisioned as a spiral, integrating both the physical body and the flow of energy within it.

Interestingly, both Eastern and Western anatomical views align with the Law of Octaves, which states that the circumference encasing each body section increases by an octave (or 6 degrees) compared to the previous one.

The Eastern anatomical concept connects the body to the natural environment in which it exists, considering elements beyond mere physiological function.

For those of us raised and educated in the West, this view may seem unusual or even challenging compared to “our” understanding of the human body.

Since shibari developed as a “technique” within Japanese Eastern culture, understanding their perspective and foundational principles can greatly enhance our comprehension.

For instance, we leverage the shared spiral structure of both the body and the rope to establish a channel for communication and control during the session.

How?

The Eastern anatomical model suggests that energy flows from the head downward to the ground in a descending spiral, then returns upward in a counter-rotating spiral.

Conversely, Western science explains that body muscles distribute weight (and gravitational force) by transferring it in a zigzag pattern from the head to the feet, returning upward in a reverse direction.

These are simply two different explanations for the same phenomenon: the torque generated by the body.

In biomechanics, torque refers to the rotational force on joints caused by muscle activity. Muscles exert forces on joints, creating torque that enables movement. The longer the lever arm, the greater the torque produced by a given muscle force.

Similarly, shibari ropes are typically braided in a spiral pattern. When correctly joined to the body, maintaining consistent tension in both creates a seamless flow of communication and management during the session.

In fact, this example encapsulates the core technical principles of the sekibaku style.

An Eastern aphorism states, “We are spirit and have a body.” This can be understood as a reminder that we bear the responsibility to care for and preserve our bodies and, naturally, those of others as well.