History of shibari without myths. Part 2: Development and spread

Shōwa Era (1926–1989)

This period marks the development of shibari, deeply influenced by the historical and social upheavals that shaped Japan.

In the early decades leading up to World War II, Japan's industrial and economic growth facilitated the proliferation of companies dedicated to the production of adult content, which reached astonishing proportions.

Japan's defeat in the war not only dealt a severe blow to the morale and values of Japanese nationalism but also led to the occupation of the country by foreign troops, primarily American forces.

Like the rest of the nation, the adult industry was quickly rebuilt, leading to the emergence of publishing houses that are now considered integral to the history of shibari.

Kitan Club and Uramado are among the most well-known names.

Many of these publications shut down during the economic crises of the 1970s, while those that survived transitioned first to video publishing and later to online platforms.

In the early post-war years, American troops stationed in Japan could not help but be amazed at the prevalence of sex-related businesses and activities that seemed to be everywhere. This was especially striking as they were in the midst of a period of moral rearmament back in the United States, where bondage photos of an innocent Bettie Page were being publicly burned.

As always, prohibition gave rise to a black market. Soon, were setting up profitable operations to smuggle Japanese pornography back to their homeland, introducing shibari to the United States.

At the time, “home” movie cameras in 8 mm and 16 mm formats gained popularity. Unsurprisingly, the Japanese industry quickly took advantage of these technological advancements to produce films at an extraordinary rate.

One significant consequence of shibari’s transition to film was the change in materials used for tying. Much like how some actors struggled with the advent of sound in cinema, the traditional thick rice ropes did not translate well on screen.

Film grain, resolution, and color processing made these ropes look coarse and unattractive. They were gradually replaced by jute ropes, which were thinner and had a golden tone that looked much more attractive when projected.

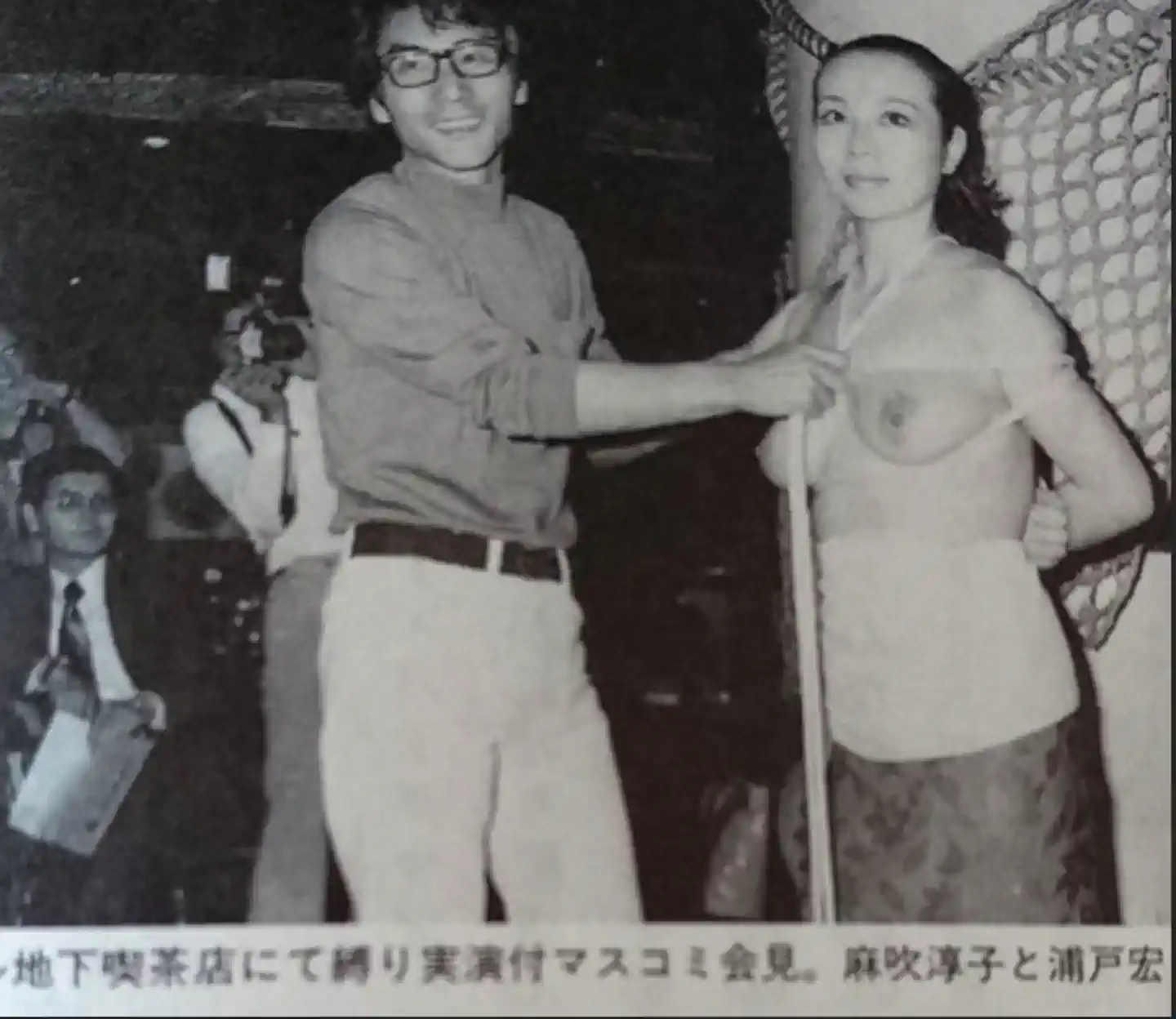

A curious anecdote from this period involves the rigger Urado Hiroshi 浦戸宏, who, when invited to tie for a film aimed at an American audience, arrived with his traditional ropes. However, the director decided that, since the magazine Bizarre featured models tied with black cotton ropes, they should use that material to better align with the preferences of their target audience.

Without delay, an assistant was sent to a hardware store to purchase several meters of cotton rope. The young man returned with the rope, but it was white. No one on the production seemed to notice the difference, and, as the Japanese are known for their frugality, the rigger used that set of white cotton ropes for many years. Over time, this became a distinctive and characteristic feature of his work.

Although the anecdote may seem trivial, it perfectly illustrates the difference in mentality and criteria between East and West.

Erotic cinema experienced a golden age in Japan with the advent of television. Traditional “entertainment” film studios couldn’t compete with the new medium, which brought stories and narratives directly into homes. However, due to censorship laws, television was prohibited from broadcasting pornography.

This gave rise to the phenomenon known as “Pinku Eiga (ピンク映画)” or “pink films,” a subgenre of Japanese cinema that emerged in the 1960s. These films are characterized by their erotic content and their exploration of fringe topics such as crime and prostitution.

But one more technological advancement was needed to once again revitalize the industry: video. The widespread adoption of video technology, both domestically and in production, provided a new boost to an already massive industry.

This format introduced a new consumption model, which would later solidify with the advent of DVDs: specialized rental stores. These stores operated on a system where the customer paid the full price for an initial purchase, followed by discounted exchanges.

In other words, a customer would buy a movie at full price, take it home, watch it, and later return it to exchange it for another title at a reduced price.

This dynamic proved to be an overwhelming success. At its peak, production companies were filming, editing, duplicating, and distributing between three and five titles every week.

Such a relentless pace inevitably meant that quality took a back seat. Often, the same film was simply re-shot multiple times with different actresses.

In the Japanese adult film industry, it is the actresses (AV idols) who sell the product. The names of riggers remain largely unknown, but having a popular actress attached to a title guarantees commercial success.

The Shōwa era is synonymous with some of the most prominent names in the history of shibari: Arisue Go, Akechi Denki, Randa Mai, Yukimura Haruki, and others.

In the later years of this era, a few figures emerged who continue to influence the rhythm and development of shibari today. These include riggers like Akechi Kanna and Naka Akira, photographers such as Norio Sugiura, and producers like Marie Aoi.

You can find more details about these masters on our blog under the tag -縛師.