History of Shibari, without myths. Part 1: Historic background.

Historical Context of Erotic Art and Bondage in Japan

While adult erotic content has been widely documented in Japan since ancient times, especially through woodblock prints known as shunga, there is no evidence of thematic series explicitly dedicated to “bondage” or erotic bondage as we understand it today.

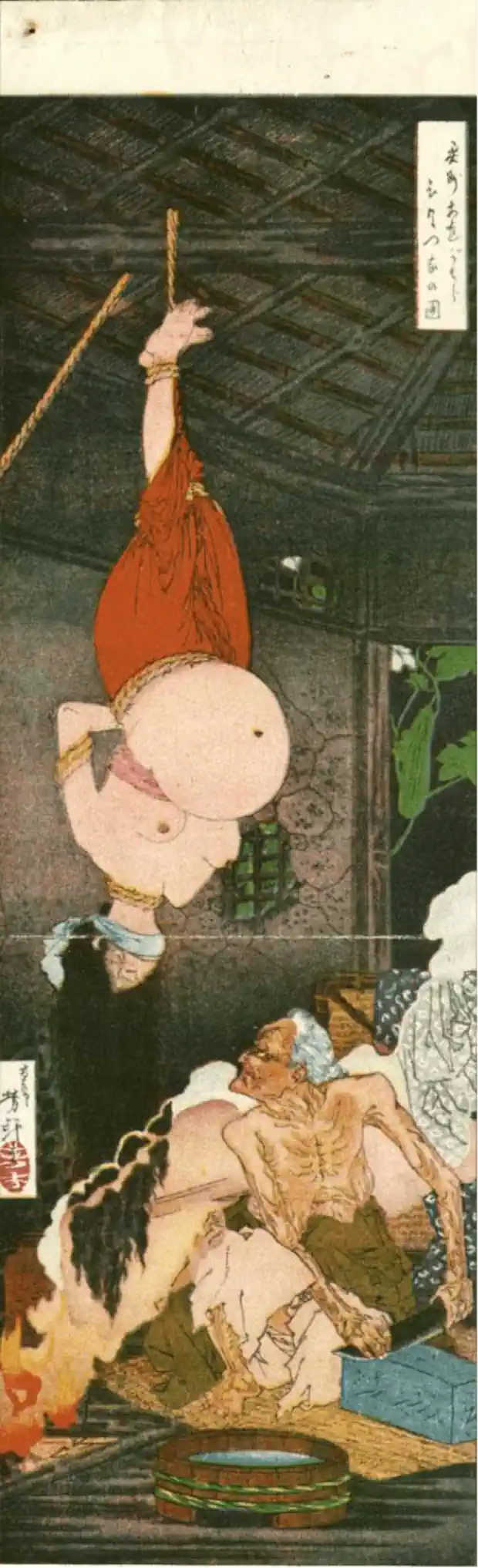

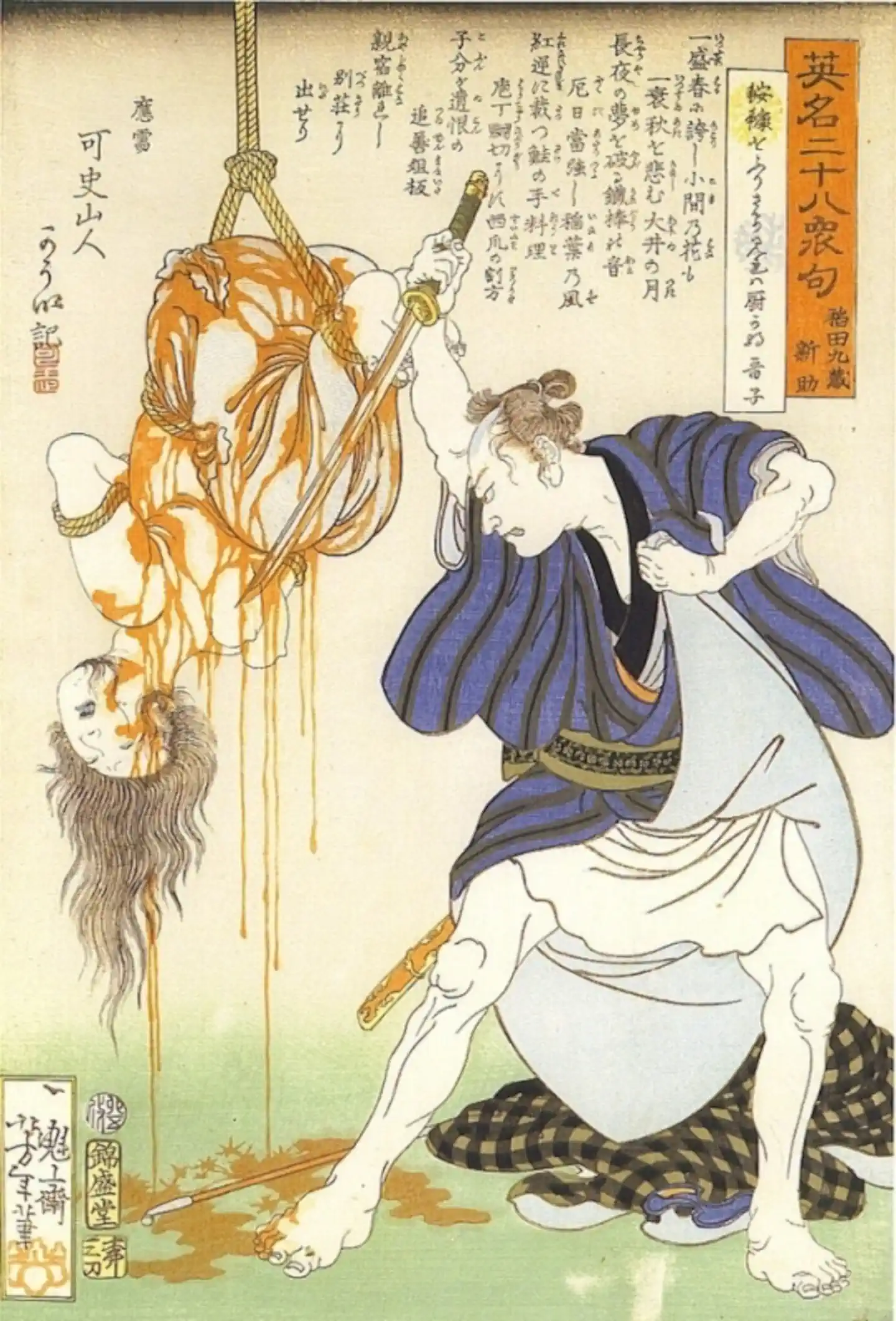

Note: It is common for fetish-oriented media and profiles to share old prints depicting bound individuals. However, these images often portray violent situations, such as kidnappings or crimes, with no connection to consensual sexuality.

A notable example is the illustration accompanying this text: The Murder of Ohagi by Saisaburô (1867), part of the series Twenty-Eight Famous Murders with Poems by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi.

The absence of bondage-themed erotic prints was likely due to the fact that such a preference was too niche to be economically viable for artisans to produce. Much like today's adult entertainment industry, the market dictated what was created, prioritizing themes that appealed to a broader audience.

Meiji Era (1868–1912)

During the Imperial Restoration, Japan adopted many customs and social norms from the West, including Puritan morality.

In 1880, the Obscenity Law was enacted — an imported concept that, when applied in Japan, lacked clear cultural coherence. Let me explain.

During the Edo period, erotic prints often depicted explicit sexual acts.

However, under Western-influenced moral standards, exposure of the genitals was considered obscene, leading to the 1907 law that explicitly banned it (a regulation that remains in effect today).

This restriction forced artists to explore new ways of expressing sexuality that would captivate their audiences without showing genitalia. While one solution was to pixelate or obscure genital areas with objects or banners, these approaches typically disrupted the erotic appeal of the images.

In contrast, shibari/kinbaku shifted the focus away from genitalia and explicit sexual acts. Instead, the erotic tension centered on the act of restraint itself or, in many cases, the depiction of violation, which became the focal point of desire.

Another significant impact of Japan’s Westernization was its rapid industrialization. In this period, the transition from traditional handcrafted woodblock printing to modern printing presses enabled mass production, that could produce thousands of copies in just hours.

This technological advancement spurred the growth of numerous publishing houses and magazines dedicated to adult content, marking a turning point in how erotic material was created and consumed.

Taishō Era(1912-1926)

It was in this period that shibari, or kinbaku, began to take shape and solidify, although it’s likely that no one referred to it by these terms at the time.

One of the most important figures of this era, often referred to as the “father of shibari,” was Ito Seiyu.

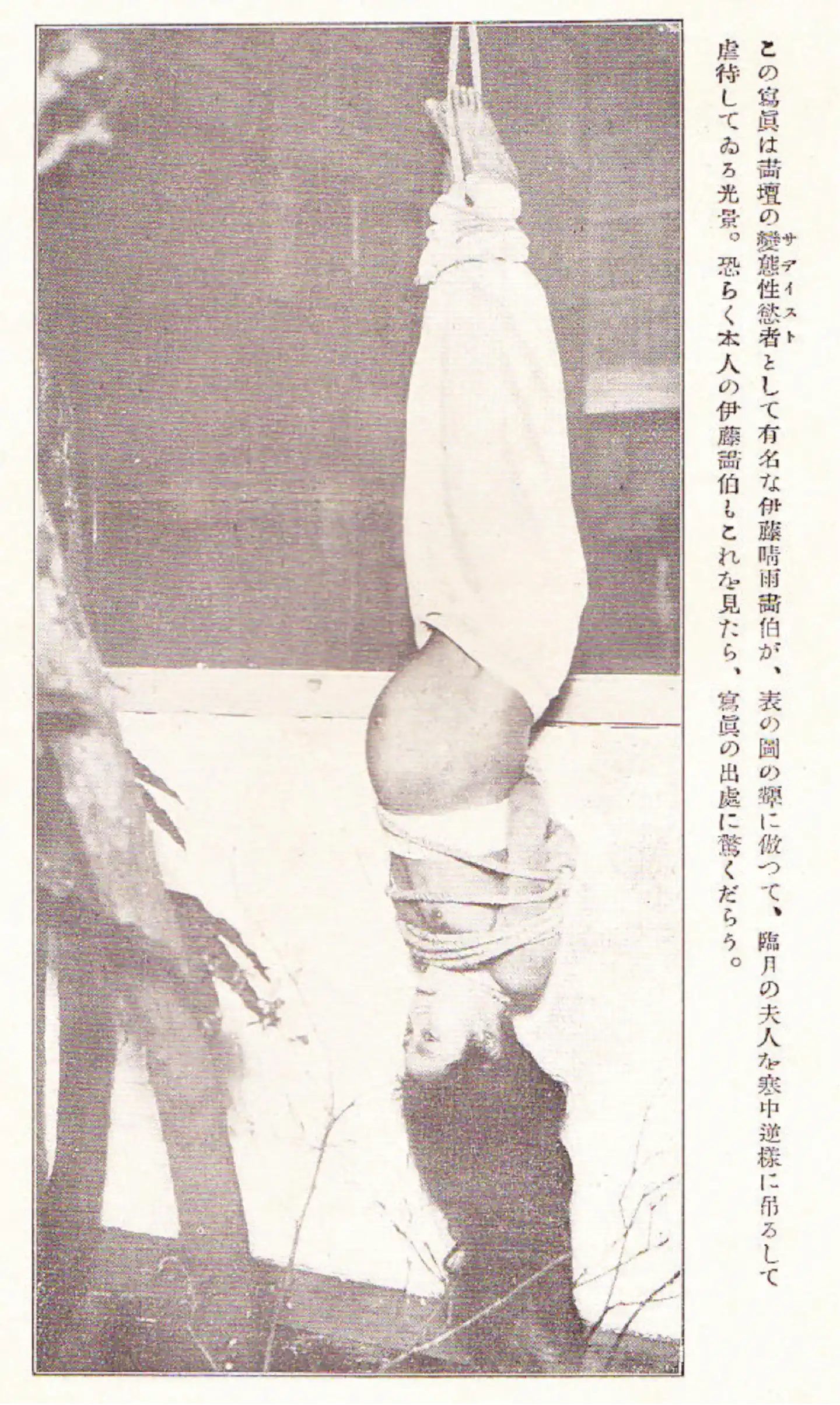

Born in 1882, Ito Seiyu was a Japanese artist whose fascination with scenes of torture emerged at an early age. His career spanned various forms of expression, including painting, photography, and theater.

He is generally considered the “father” of shibari due to his status as the most recognized and popular author of his time, as well as being one of the first to focus his work on bondage for sexual purposes.

During the Taisho era (1912–1926), Ito worked as an illustrator and theater critic. In this period, he delved deeper into photography, specializing in themes related to torture, and became part of the eroguro movement, an artistic trend that blended eroticism with grotesque and absurd elements, challenging the rigid moral and social norms of the time.

His first book on shibari, “Seme no Kenkyu” (Study of Torment), was published in 1928. Although it was soon banned for violating the moral standards of the era, it has been reprinted several times and is now a key reference for enthusiasts and collectors of shibari memorabilia.

Ito reached the peak of his career before World War II, publishing numerous graphic works and creating theater groups focused on torture scenes.

After the war, Ito reinvented himself as a writer for magazines and continued with his photography sessions. In 1953, he founded Seme no Gekidan (The Theater Group of Torment), which performed in numerous Tokyo theaters.

One of his great passions was traditional craftsmanship and tools, which is reflected in his tying style. His work clearly demonstrates the influence of guild techniques on shibari.

Ito Seiyu stands as a key figure of the Taisho era, a period of transformation in Japanese society. By challenging taboos and exploring subjects considered disturbing, he became a pivotal figure in the future development of shibari.

Towards the end of the Taisho era, the “EroGuro Nansensu” movement emerged, which can be translated as “Erotic Grotesque Nonsense”.

Influenced by subversive and innovative Western trends, this artistic movement effectively reflected the social anxiety of the time with its mixture of eroticism, grotesqueness, horror, and absurdity.

A key figure in this movement was the writer Edogawa Rampo, a pioneer of Japanese detective fiction and creator of memorable characters like Detective Kogoro Akechi (Detective Conan is a tribute to this character).

In this era, censorship drove new forms of erotic expression, and the turbulent social context opened the door to the grotesque—combining the repulsive with the alluring, pleasure with suffering, desire with fear.

Another element that emerged during this period was harm to the body. In Europe during the Belle Époque, shows featuring fakirs and acts of self-mutilation were popular.

In Japan, legal ambiguities led this facet to find expression in the art world. If it was a drawing or a photo, there was no physical body, and thus no crime.

This is an important point to consider, as it influences the perception of shibari. Extending this “artistic” concept to the “erotic” realm has led some to mistakenly believe that harm to the body is an inherent part of this erotic expression—an error in understanding.

Obra claramente inspirada en “The Lonely House on Adachi Moor” (奥州安達が原ひとつ家の図)” de Tsukioka Yoshitoshi -1885.